Indicators

Topic 6: Rental reform

In Topic 3: Rental affordability, we highlighted the rental affordability crisis facing Tasmanians, fuelled by rapid and sustained rental increases over the past decade. Below, we make some comparisons with other Australian states and territories and highlight the need for robust rental protections and rights in legislation, to ensure that renting a home is a secure and enjoyable housing option for all Tasmanians.

In Australia, private rental has grown faster than any other housing tenure type over the past 20 years, driven by declining and delayed entry into home ownership and the contraction of social housing.[1] Renting a home is no longer a short-term option for many students, young people and low income earners, such that the number of lifelong renters in this country is growing.[2] While there is an increasing number of middle-class renters in Australia, renting also continues to be a critical housing tenure choice for people on low incomes, most of whom are priced out of buying a house and cannot readily access social housing.[3]

Renting does have some obvious benefits, including flexibility to relocate without significant financial penalties (such as paying stamp duty on the sale and purchase of property) and greater labour mobility.[4] However, home ownership is still seen as desirable in Australia because it offers a sense of security of tenure, housing stability and enduring connection to a particular neighbourhood.

However, renting would not be a ‘second-best’ housing outcome for people if there was tenure equity in Australia — in which similar social and economic benefits would be derived from different tenure choices such as renting or home ownership.[5] While “security, stability and a sense of belonging can be characteristics of rental housing under appropriate regulatory settings,” that’s not what most Tasmanian renters experience. [6]

In response to growing calls for action, governments have implemented a wave of reforms to residential tenancy acts in Australian jurisdictions in the 2020s, formalised by National Cabinet agreeing to ‘A Better Deal for Renters’ which is designed to harmonise and strengthen renters’ rights across Australia.[7]

References:

[1] Pawson, H, Milligan, V & Yates, J (2025), Housing Policy in Australia: A Case for Reform, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 340.

[2] Parliament of Australia (2025), Implications of Declining Home Ownership, Department of Parliamentary Services, May.

[3] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2025), Home Ownership and Housing Tenure, October.

[4] Parliament of Australia (2025), Implications of Declining Home Ownership, Department of Parliamentary Services, May.

[5] Pawson, H, Milligan, V & Yates, J (2025), Housing Policy in Australia: A Case for Reform, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 340.

[6] Pawson, H, Milligan, V & Yates, J (2025), Housing Policy in Australia: A Case for Reform, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 340.

[7] Prime Minister of Australia (2023), ‘Meeting of National Cabinet: Working together to deliver better housing outcomes,’ media release, 16 August.

Tasmania’s Residential Tenancy Act 1997 (Tas) is due for periodic review in 2027.[1] In August 2025, the Tenants’ Union of Tasmania sent a letter to all newly elected members of the House of Assembly calling for a comprehensive review of the Act as a matter of urgency and increased funding for tenant advocacy services.[2] This called was echoed by other housing advocates, including Shelter Tasmania and TasCOSS.

In September 2025, the Attorney-General, Hon Guy Barnett MP, told Parliament that “a comprehensive wholesale review of the residential tenancy legislation” will commence in early 2026.

This year, some progress has been made towards providing stronger rental protections and rights for Tasmanian tenants, as follows:

- Pets in rentals: The Residential Tenancy Amendment (Pets) Bill 2025 has passed the Tasmanian Parliament.[3] Once enacted, this amendment will mean that only the Tribunal can determine that a pet cannot be kept of the premises.[4]

- Safety amendments: The Residential Tenancy Amendment (Safety Modifications) Bill 2025 is currently before the Parliament. If passed and enacted, this amendment would permit tenants to make safety modifications to their rental home and only seek consent where that modification will cause permanent damage.[5]

- Caravan park residents: In its latest 100 Day Plan covering 29 November 2025 to 9 March 2026, the Tasmanian Government has committed to introduce legislation to protect the rights of long-term residents in caravan parks.[6]

However, there is still a compelling need for the Residential Tenancy Act 1997 (Tas) to be significantly revised to ensure better protections for Tasmanian renters, especially in relation to:

- Reasonable grounds for evictions;

- Retaliatory eviction provisions;

- Rent controls;

- Bans on unsolicited rent bidding;

- Domestic and family violence protections;

- Limits on break-lease fees;

- Protections for renters’ personal information;

- Minimum rental housing standards, especially energy efficiency;

- Regulation of short-stay accommodation;

- Marginal or vulnerable renters in boarding or rooming houses; and

- Protections for social housing tenants.[7]

References:

[1] For more information, please see Residential Tenancy Act 1997 (Tas).

[2] Tenants’ Union on Tasmania (2025), ‘Call for review of the Residential Tenancy Act 1997 (Tas),’ media release, 8 August.

[3] Premier of Tasmania (2025), ‘Working to allow pets in rentals,’ media release, 12 November

[4] Tasmanian Government (2025), Residential Tenancy Amendment (Pets) Bill 2025 fact sheet.

[5] For more information, please see Residential Tenancy Amendment (Safety Modifications) Bill 2025.

[6] Tasmanian Government (2025), Our 2030 Strong Plan for Tasmania’s Future: The Next 100 Days (29 November 2025-9 March 2026).

[7] Shelter Tasmania (2025), The Rental Report: A 2 Year Performance Report on the Progress of A Better Deal for Renters.

Headline indicators:

- The proportion of the Tasmanian population who rent from private landlords (rather than renting social housing, buying a house with a mortgage or owning their home outright) increased by 50% from 14.6% in 1994-95 to 21.7% in 2019-20 [latest available figures].

- The average length of time for median income earners in Australia to save a 20% deposit to buy a home was 10.6 years in 2024, a near record high.

Figure 6.1: Between 1994-95 and 2019-20, ABS data shows that the proportion of households renting social housing or were homeowners without a mortgage both fell, while the proportion of households who were homeowners with a mortgage or renting from a private landlord both rose.

Figure 6.2: In the past 12 months, Hobart’s rent prices for both houses and units have continued to increase (by 6% and 11% respectively), which is a faster growth rate than all other capital cities other than Perth.

Figure 6.3: The SGS Rental Affordability Index shows that rents are either unaffordable or moderately unaffordable in every jurisdiction (with an index Score below 121), except for the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). Importantly, this data also shows there is a positive relationship between rental rights and rental affordability. While Victoria and the ACT have the strongest rental rights of all jurisdictions, they also have the best rental affordability nationally: the ACT ranks first (with an Index score of 133) and Melbourne second (with an Index Score of 118).

Figure 6.4: Victoria generally has the strongest tenant protections in Australia. In comparison with other jurisdictions, Tasmania has made some recent improvements to key rental protections and rights, but evictions at the end of fixed terms (with no specific reason) are still allowed.

Tasmanians are currently facing a dual crisis of housing affordability and tenure insecurity. While other Australian jurisdictions — notably Victoria, Queensland, South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory — have recently moved to modernise their residential tenancy acts, Tasmania is at risk of falling behind. Despite recent legislative attention, significant gaps remain that leave Tasmanian renters vulnerable to arbitrary eviction, substandard housing conditions, and unpredictable housing costs.

Given that more Tasmanians on low incomes are expected to be renting their homes for longer periods of time, and perhaps for their lifetime, the quality of that housing experience is arguably more important than ever. A critical way to improve people’s experience is to ensure that adequate rental protections and rights are in place which increase security of tenure and ensure minimum housing standards. While vacancy rates in Tasmania are at record-lows and amongst the lowest nationally, the power differential between tenants and landlords remains significant.

The upcoming review of the Residential Tenancy Act 1997 (Tas) presents a critical opportunity to reset this relationship. As Dr Jed Donoghue from The Salvation Army Tasmania has noted, “reasonable people realise that it is important to maintain a tenancy system that protects both tenants and landlords and enables people who rent their homes to lead healthy, safe and productive lives.”[1]

[1] Council to Homeless Persons (2023), Parity: Reforming Residential Tenancy Acts, June, vol. 26, no. 4.

TasCOSS is calling on the Tasmanian Government to:

- Review and reform the Residential Tenancy Act 1997 (Tas) to provide better protections and rights for Tasmanian renters, especially in relation to no-grounds evictions and rental increases.

- Ensure the Tenants’ Union of Tasmania has adequate long-term, core funding to deliver essential legal services for renters in the North and North-West, at an estimated cost of $300,000 per annum.

For TasCOSS’s recommendations about rental affordability, see Topic 3: Rental affordability.

[1] consumer.vic.gov.au/housing/renting/new-changes-to-the-rental-laws

[3] act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/2608620/The-Renting-Book-November-2025.pdf

[5] cbs.sa.gov.au/documents/tenancy/guides/Tenant-Information-Guide.pdf

[6] nsw.gov.au/housing-and-construction/renting-a-place-to-live/during-a-residential-tenancy

[7] nsw.gov.au/housing-and-construction/rules/minimum-standards-for-rental-properties

[8] cbos.tas.gov.au/topics/housing/renting

[9] cbos.tas.gov.au/topics/housing/renting/beginning-tenancy/minimum-standards/types

[10] rta.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-09/Form-17a-Pocket-guide-for-tenants-houses-and-units.pdf

[11] rta.qld.gov.au/before-renting/preparing-for-a-tenancy

[12] consumerprotection.wa.gov.au/landlord-ending-tenancy

[13] consumerprotection.wa.gov.au/system/files/documents/2025-10/landlordsguide.pdf

See also: National Shelter (2025), The Rental Report: A 2 Year Performance Report on the Progress of A Better Deal for Renters.

Topic 5: Disability and housing

People with disability in Australia face greater housing disadvantage or insecurity than the general population and are disproportionately impacted by the current housing crisis. Challenges for people with disability include higher rates of housing stress, lower rates of home ownership, greater need for social housing and increased risk of homelessness.

The vast majority of disabled people in Australia live in the community rather than in care accommodation: nationally, 96% of people with disability live in the community in private dwellings. See: AIHW (2024), People with disability in Australia.

Housing disadvantage for people with disability is underpinned by systemic inequalities, including income inequality: people with disability are four times more likely to rely on inadequate government income support and are twice as likely to live in low income households. See: AIHW (2024) People with disability in Australia; and Centre of Research Excellence in Disability and Health (2024) Housing and income of adults with disability in Australia.

Another significant factor underpinning housing disadvantage for people with disability is the lack of supply of homes that are designed or adapted to meet the needs of people with disabilities. These issues include physical access related to doorways, bathrooms and kitchens, as well as sensory and cognitive accessibility. For those renting, landlords frequently refuse requests from tenants to install accessibility aids, such as grab rails.

At the national level, housing is clearly identified as a key policy issue for people with disability. The national disability policy framework is laid out in Australia’s Disability Strategy (2021-31). The Plan is supported by an Outcomes Framework which includes two housing priorities: “improving access to affordable housing for people with disability,” and “making sure people with disability can live in homes that meet their needs.” See: AIHW, Outcomes Framework: Inclusive homes and communities.

The Strategy’s associated Inclusive Homes and Communities Targeted Action Plan (2025-27) aims to: improve housing accessibility; reduce wait times for social housing; and increase satisfaction with housing among NDIS participants. See: Disability Gateway, Inclusive Homes and Communities Targeted Action Plan (2025–27).

At the state level in Tasmania, housing is identified as a policy priority for people with disability, with Tasmania’s Disability Strategy (2025-27) including two housing policy priorities:

- Increase the availability of affordable housing.

- Housing is accessible and people with disability have choice and control about where they live, who they with, and who comes into their home.

In October 2024, the Tasmanian Government committed to a phased rollout of the Livable Housing provisions in the National Construction Code between October 2024 and October 2026. This requires almost all new building work for housing to progressively comply with accessibility standards, including for door openings, showers, bathroom walls, and internal door and corridors. See: Australian Building Codes Board, Livable Housing Design Standards.

Homes Tasmania has committed to “deliver all new social housing homes at Silver standard wherever practical, and to Gold or Platinum standard where appropriate.” See: Homes Tasmania Dashboard (July 2025).

Updated on 10 December 2025 with the latest available data.

Headline indicators:

- Anglicare’s Rental Affordability Snapshot, taken for a weekend in March 2025, found that 0% of houses for rent in Tasmania during the snapshot weekend were affordable for single people (aged 21+ years) who were receiving Disability Support Pension.

- In 2022, one third (33%) of individuals and families in Australia who were receiving both Commonwealth Rent Assistance and Disability Support Pension were in rental stress (i.e. paying more than 30% of their income on housing).

- As at 31 October 2025, 22.5% of applicants waiting for social housing in Tasmania may have accessibility needs (i.e. older people aged 75+ years and/or those who require property modifications for accessibility).

Figure 5.1: According to data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers 2022, Tasmania has the highest estimated proportion of the population with disability at 28.8%. The jurisdictions with the equal second highest rates of disability are Queensland and South Australia, at 23.3%.

Updated on 10 December 2025 with the latest available data.

Figure 5.2: For each type of housing security — ‘homeowners,’ ‘never been homeless’ and ‘not in housing stress’ — people with disability are less likely to be housing secure than people without disability. Source: Disability and Wellbeing Monitoring Framework.

Figure 5.3: Tasmania has the highest rate of people receiving Specialist Homelessness Services support who are also NDIS participants (8.4%), higher than the national average of 5.8%.

Figure 5.4: From 1 October 2020 to 31 October 2025, Homes Tasmania delivered 2,150 social houses, of which 73% were built to the Silver accessible standard or above. The breakdown is:

- 1,311 to Silver accessible standard;

- 188 to Gold accessible standard;

- 77 to Platinum accessible standard or above;

- 329 did not meet the standard; and

- 245 homes were built to an unknown standard.

Tasmania’s ageing population means that the proportion of the population with disability is likely to continue to grow, which is reflected in growing demand for affordable and accessible housing for people with disability. There’s a critical need for housing, including social housing, in Tasmania to be more affordable and accessible for people with disability.

The Tasmanian Government has a critical role in providing leadership for improved housing security for people with disability, by providing policy direction for all housing stakeholders; and setting minimum design standards for new housing construction. The forthcoming Disability Inclusion Action Plan for Tasmania should include housing as a key priority; and the current Tasmanian Housing Strategy could be complimented by a dedicated Accessible Housing Strategy which is co-designed by people with disability.

Additionally, TasCOSS is calling on the Tasmanian Government to ensure the building and construction industry complies with the full suite of Livable Housing Design Standards according to the agreed timeframe, and all future social housing homes delivered by Homes Tasmania should meet at least the Gold level. As well, the Tasmanian Government should look to amend the Residential Tenancy Act 1997 (Tas), as part of a wider review of this Act, to ensure that tenants are permitted to modify their rental properties to install accessibility features and have assistance animals in their homes.

TasCOSS is calling on the Tasmanian Government to:

- Implement the full suite of Livable Housing Design Standards level Silver by no later than October 2026.

- Ensure that all future social housing homes delivered by Homes Tasmania meet at least the Gold level of the Livable Housing Design Standards.

- Pursue legislative changes to ensure tenants can install accessibility features such as grab rails and step ramps in rental properties and have assistance animals in their home.

- Identify equitable access to appropriate and affordable housing as a key objective of the forthcoming Tasmanian Disability Inclusion Action Plan.

- Co-design a dedicated Accessible Housing Strategy with people with disability which compliments the Tasmanian Housing Strategy.

Topic 4: Child and youth homelessness

Tasmania has a growing homelessness problem which impacts hundreds of children and young people. In 2021, 2,350 people were homeless on Census night — an increase of 45% since the 2016 Census. In 2021, 911 (39%) of homeless Tasmanians were children and young people aged 0-24 years.[1] Many children and young people who are homeless are accompanied by a parent or another protective adult, but others are alone (or unaccompanied) while homeless, making them even more vulnerable.

See our Glossary for how we have classified children and young people for the Tasmania’s State of Housing Dashboard.

Homeless children and young people might be:

- Staying in supported accommodation for homeless people;

- Sleeping in temporary accommodation;

- Couch surfing;

- Sleeping on the street or in a park; or

- Living in severely crowded dwellings.

See our Glossary for definitions of homelessness.

Homelessness is a problem because it can “profoundly affect a person’s mental and physical health, their education and employment opportunities, and their ability to fully participate in society.”[2] These effects are particularly damaging for children and young people, and include malnutrition, poor dental health, developmental delays and depression and anxiety, social disconnection and loneliness, as well as significant threats to physical and sexual safety.[3]

For insights into Tasmanian children’s experiences of home and homelessness, see Bessell, S, O’Sullivan, C & Lang, M (2024), More for Children Issues Paper: Housing, Children’s Policy Centre, Australian National University.

References:

[1] ABS, Census data from 2016 and 2021, Homelessness.

[2] AIHW, Specialist homelessness services 2023/24: Tasmania.

[3] Mission Australia (2025), ‘Homelessness and its lasting impact on children and young people,’ media release.

Additionally, many children and young people who are homeless and unaccompanied have had traumatic experiences before leaving home, including:

- Domestic and family violence;

- Physical and emotional abuse;

- Sexual abuse;

- Homophobia and transphobia;

- Neglect and abandonment; and/or

- Poverty. [1]

A mix of homelessness and housing services for children and young people is delivered in Tasmania, most of which are funded by Homes Tasmania. These include:

- Youth2Independence facilities: For young people who are “ready to participate in education, training or employment” in Launceston, Devonport, Burnie and Hobart. See: Homes Tasmania, Youth2Independence.

- Youth2Independence homes: Cluster homes or shared homes for young people who “will benefit from living in a small, home-like environment” in Burnie, Devonport, Launceston and Clarence LGAs. See: Homes Tasmania, Youth2Independence.

- Backyard units: Demountable dwellings for young people, available for households of four or more people, living in social housing owned by Homes Tasmania, with at least one person aged 15-25 years. See: Homes Tasmania, Backyard Units.

- Medium- to longer-term accommodation: Accommodation in Kingston for young people aged 12-15 years who are homeless or at risk of being homeless. Funded by the Department for Education, Children and Young People. See: Mission Australia, Kingston House.

- Crisis and transitional accommodation: A mix of accommodation in the south, north and north-west of Tasmania for either: (a) unaccompanied children aged 12-15 years; or (b) young people aged 13-20 years. See: Homes Tasmania, Housing Connect.

There is also a mix of support services targeted to children and young people in Tasmania who are either homeless or at risk of homelessness, such as rental subsidy programs or intensive youth support services, which are generally delivered by community service organisations.

Reference:

[1] Homelessness Australia (2023), Child and youth homelessness fact sheet.

Updated on 10 December 2025 with the latest available data

Indicators:

- In March 2025, 222 children (aged 0-14 years) and 538 young people (15-24 years) were clients of Specialist Homelessness Services in Tasmania.

- In 2023-24, 1,464 young people (15-24 years) presented alone to Specialist Homelessness Services in Tasmania.

- In the September quarter of 2025, 42 unaccompanied children under 18 years of age sought housing assistance from Housing Connect, the housing entry point for people experiencing homelessness or in housing need, delivered by Anglicare Tasmania.

- As at 31 October 2025, there were 1,152 young people as primary applicants waiting for social housing.

See our Glossary for an explanation of Specialist Homelessness Services.

Figure 4.1: Between 2020 and 2024, the number of young people as the primary applicant who were waiting for social housing increased by 16% from 886 to 1,027. In the same period, the number of young people waiting for social housing increased by 27% from 1,208 to 1,540.

Figure 4.2: In 2023-24, Tasmania’s rate of young people presenting alone to Specialist Homelessness Services (231.7 clients per 10,000 people) was the second highest of all states and territories, after the Northern Territory.

Figure 4.3: From 2011-12 to 2023-24, Tasmania’s average annual increase in young people presenting alone to Specialist Homelessness Services (1.2%) was the second highest of all states and territories. In the same period, Victoria, Western Australia, South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory each showed an average annual decrease in young people presenting alone.

Figure 4.4: During 2023-24, Specialist Homelessness Services in Tasmania reported 11,181 unassisted requests for homelessness services. Of these, 6,759 unassisted requests (61%) were for children and young people (0-24 years), compared to 46% of unassisted requests nationally.

Figure 4.5: According to AIHW data released in August 2025, 1,296 children aged 12-17 years were receiving support from Specialist Homelessness Services in Tasmania in 2023-24. Of those, 480 children (37%) were unaccompanied by an adult. This was the highest number of unaccompanied children receiving homelessness support in Tasmania for at least the past five years.

Figure 4.6: Nearly six-in-ten (58%) unaccompanied children receiving Specialist Homelessness Services in Tasmania had one or more of three selected vulnerabilities: mental health issues; family and domestic violence; and problematic drug and/or alcohol use.

Figure 4.7: Each year since 2019-20, Tasmania has had the highest rate of unaccompanied children receiving support from Specialist Homelessness Services compared to all other states and territories, except the Northern Territory (excluded from Figure 4.7 due to data issues).

Despite the mix of accommodation and support services delivered to children and young people in Tasmania, this cohort still experiences a significant problem with homelessness. This is demonstrated by the data, including: Tasmania’s high rate of children and young people receiving support from homelessness services; and the growth in the number of children and young people receiving support alone. The homelessness system in Tasmania is simply not adequately resourced to meet the needs of children and young people — in 2023-24, 61% of people turned away from homelessness services were aged under 25 years.

At a strategic level, the Tasmanian Government needs to urgently develop a dedicated Child and Youth Action Plan for Homelessness, which would prioritise the specific care needs of children and young people. This Plan should include specific commitments to deliver more specialist support services and accommodation to homeless children and young people who are unaccompanied or have other complex needs. As well, the plan should aim to foster better coordination of universal child- and youth-centred services, such as education, family support, mental health and child protection, so as to increase efforts to prevent homelessness for children and young people.

Children and young people face significant barriers to accessing housing and homelessness services. Private rentals are often inaccessible for a young person who, by virtue of their age, usually lacks a good rental or employment history to support their application. For all Tasmanians, social housing is not really a viable housing option, given the growth in the number of applications on the waitlist (over 5,100 in June 2025) and the long wait time to be allocated social housing (over 18 months for priority applicants in June 2025). Young people experience a further barrier to accessing social housing as their very low income if receiving Youth Allowance and uncertain access to Commonwealth Rent Assistance means social housing providers may not see young people as financially viable tenants. Even if young people can access social housing, it may not be a good fit for them, with limited opportunities for living in shared housing.

Additionally, there is a general lack of medium- to longer-term housing options for children and young people who need support, which risks excluding them from stable and secure housing until they are deemed ‘housing ready.’ Young people who have high support needs (e.g. due to mental health, trauma or substance use) are usually ineligible for independent youth housing offered in Tasmania.

Unfortunately, given health system constraints in Tasmania, many ineligible young people will struggle to access the psychological or alcohol and other drug services they need to improve their health and wellbeing and thus make them eligible for Youth2Independence housing. See: Robinson, C (2022), Bigger, Better Stronger: Final Report, Anglicare Tasmania.

With regards to crisis and transitional accommodation for children and young people in Tasmania, there is an obvious need for adequate government funding to enable organisations to operate these services with a staffing model which can support the safety and wellbeing of both clients and staff.

TasCOSS calls on the Tasmanian Government to:

- Develop a dedicated Child and Youth Homelessness Action Plan to better coordinate services for homeless children and young people, especially those with unaccompanied or other complex needs.

- Strengthen child and youth homelessness prevention and early intervention by investing in family and educational supports, adolescent mental health care, tenancy support and dedicated youth social housing.

- Expand homelessness support and accommodation services for children and young people, across the housing and support spectrum.

- Adequately fund crisis and transitional accommodation for children and young people to ensure the safety and wellbeing of clients and staff.

Topic 3: Rental affordability

Tasmania is experiencing a rental affordability crisis, which mirrors the general situation nationally.

While private residential rental increases in Tasmania are showing signs of levelling off, median rents increased very sharply (by 21.5%) over two years, from June 2020 to June 2022. Growth in median rents continued to 2025. The growth since 2020 has outpaced growth in median household income in Tasmania. Rents in Tasmania are now only 10% lower than the Melbourne median, despite the average rental household income in Tasmania being 18% lower than in Melbourne. See: Latest Insights into the Rental Market, Australian Bureau of Statistics and SGS Rental Affordability Index 2024.

Steep rental price increases have meant that lower income Tasmanians are struggling to afford their rent. For the lowest income households, this is pushing people into housing stress, overcrowded housing or homelessness.

Anglicare Tasmania has observed that this rental affordability crisis is also a barrier to addressing important social issues, including “domestic and family violence, bed-block in the public hospital system and persistent disadvantage.” See: Rental Affordability Snapshot 2025, Anglicare Tasmania.

Homes Tasmania’s dashboard highlights a correlation between the median rent price and the number of people on the social housing waitlist, which is causing wait times for social housing to grow. See: Indicator 1, Homes Tasmania Dashboard; and Topic 1: Waiting for social housing, Tasmania’s State of Housing Dashboard.

An underlying issue is the very low rental vacancy rate in the state’s three major population centres of Burnie, Hobart and Launceston. This very low vacancy rate indicates that the relationship between the number of available rentals is far lower than the number needed to meet demand for rental housing, and market power is tipped in favour of landlords. Under these conditions, prospective tenants are faced with few housing options to choose from and little opportunity to negotiate a lower rent.

Updated on 10 December 2025 with the latest available data.

Headline indicators: For the second year running, Anglicare Tasmania’s Rental Affordability Snapshot 2025, found that 0% of properties listed in March 2025 were affordable for Tasmanians who were:

- Families relying on Single Parenting Payment;

- People relying on Disability Support Pension;

- Single people receiving JobSeeker;

- Young people receiving Youth Allowance; or

- Single people relying on the Age Pension wanting a place of their own.

Rental vacancy rates in Tasmania’s three main population centres of Burnie, Launceston and Hobart are well below the healthy target rate of 3% and are hovering close to zero.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the median residential rent for Tasmania grew by 43% from 2020 to 2025. Over the same period, Tasmania’s population only increased by 6.5%.

Figure 3.1: The Tenants’ Union of Tasmania Median Weighted Index of Rents has increased 3.7% over the past 12 months, with residential rent prices increasing the most in the North-West (up 10.5%).

Figure 3.2: According to the SGS rental Affordability Index for 2025, renting a home in Greater Hobart or the rest of Tasmania is extremely unaffordable for a single person on benefits as they need to spend 71% of their income if renting in Greater Hobart or 61% in the rest of Tasmania. As well, pensioner couples, single pensioners and single part-time worker parents on benefits would also find rents unaffordable, severely unaffordable or extremely unaffordable in either Greater Hobart or the rest of Tasmania.

See our Glossary for an explanation of rental stress.

Updated on 10 December 2025 with the latest available data.

Figure 3.3: Anglicare Tasmania’s Rental Affordability Snapshot for March 2025 found that only 13 advertised rental properties were affordable and appropriate for single people receiving Youth Allowance, JobSeeker Payment, Disability Support Pension or Parenting Payment Single or a couple with both receiving JobSeeker Payment.

Figure 3.4a and 3.4.b: Homes Tasmania’s Private Rental Incentives Scheme (PRIS) and Family Violence Rapid Rehousing program both “provide access for people on the Housing Register into the private rental market by head leasing properties and subsidising the rent amount, so they are affordable.” See: Affordable private rentals, Homes Tasmania.

On 1 July 2024, Homes Tasmania set higher targets of 400 homes for PRIS and 150 homes for Family Violence Rapid Rehousing by 30 June 2026. As at 31 October 2025, there were only 225 homes in PRIS (56% of the target) and 43 homes in Rapid Rehousing (29% of the target).

The crisis in rental affordability is not unique to Tasmania — it is a nationwide phenomenon which is complicated by three levels of government being involved in housing policy. That said, Tasmania has experienced a particularly severe reduction in rental affordability since 2020, compounded by having lower median household incomes than nationally. See: SGS Rental Affordability Index 2024.

Home ownership rates in Australia have declined significantly, driving a corresponding increase in the proportion of renters, especially among younger people. Rental affordability is a key issue for socio-economic equity because Australia renters are more likely than homeowners to be Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders, single parents, unemployed, international students or immigrants. The proportion of older women renting due to family separation is also rising. See: Implications of declining home ownership, Parliamentary Library.

One priority of the Tasmanian Housing Strategy is to “improve private market affordability and stability” including through the objective of “continuing to help Tasmanians in rental stress and encouraging existing and prospective property owners to increase the supply of affordable and secure rentals.”

Homes Tasmania’s Key Performance Indicator 5 is to “deliver more affordable rentals,” through their PRIS and Family Violence Rapid Rehousing programs. By their own metric, Homes Tasmania is not delivering on this objective, as the number of homes in these programs have decreased since the targets were boosted in 2024. While a combined total of 268 affordable rental homes had been delivered by 31 October 2025, when compared to the estimated 44,000 private rentals in Tasmania, it is apparent that these programs are insufficient to significantly improve rental affordability in this state. See: Renting in Tasmania, Shelter Tasmania.

Rental affordability is a complex, multi-factorial problem. Responding to it effectively will require the Tasmanian Government to pull multiple different policy levers which influence the private rental market well beyond the delivery of niche rental affordability programs which reach only a few households.

TasCOSS is calling on the Tasmanian Government to implement more ambitious policy reforms aimed at increasing the supply of private rentals, providing better protections for renters and reducing rental prices.

TasCOSS is calling on the Tasmanian Government to:

- Introduce comprehensive reforms to significantly improve rental affordability in Tasmania, particularly for Tasmanians living on low incomes.

- Review the offerings of PRIS and the Family Violence Rapid Rehousing program, with a view to increasing uptake by landlords.

- As part of the legislative review slated for early 2026, strengthen the Residential Tenancy Act 1997 (Tas) to provide better protections for renters, especially in relation to no grounds evictions and rental increases.

- Better regulate short-stay accommodation to limit the permitting of whole-homes in areas with low rental vacancy rates.

See also TasCOSS’s recommendations for Topics 1 and 2.

Update on recommendation #3

In September 2025, Attorney-General, the Hon Guy Barnett told Parliament:

“With respect to the review, it is my intention to bring forward that review with the start date of the review of the Residential Tenancy Act (Tas) to begin at the start of next year. The department is in the early stages of preparing a discussion paper for release in early 2026.”

TasCOSS welcomes the Government’s intention to review the Residential Tenancy Act 1997 (Tas) in 2026, and we look forward to participating in this review. As outlined, key reforms needed include limiting rent increases to defined periods and reflecting genuine cost increases, eliminating no-grounds evictions, and strengthening rights for tenants to make minor modifications to their rental properties.

Topic 2: Progress on the Homes Tasmania targets

The Tasmanian Government’s Tasmanian Housing Strategy (the Strategy) sets an ambitious vision “to end homelessness by improving the entire housing system and ensuring all Tasmanians have access to safe, appropriate and affordable housing.”

The Strategy makes several commitments:

- Deliver more quality homes, faster;

- Support people in need;

- Improve private market affordability and stability; and

- Enable local prosperity.

The Tasmanian Government has promised to deliver a range of housing for Tasmanians, covering crisis accommodation, social housing including specialist and supported accommodation, affordable rentals, affordable home purchases and affordable land lots.

The Strategy includes a target of delivering 10,000 social and affordable homes by 2032, including a sub-target set in 2023 of 2,000 additional social homes by 2027

However, it is important to note that the Tasmanian Government did not promise to deliver — and is not delivering — 10,000 new homes.

See our Glossary for an explanation of the types of housing support delivered in Tasmania.

Updated on 10 December 2025 with the latest available data.

Indicators:

As at 31 October 2025:

- Homes Tasmania has completed a total of 4,480 homes and land lots, of which only 2,170 are social housing homes and supported accommodation.

- There are another 5,516 deliverables in Homes Tasmania’s current pipeline.

- There is no longer a separate concept phase.

Key changes to reporting:

Homes Tasmania has introduced new reporting of the deliverables in its housing plan. The July 2025 Homes Tasmania Dashboard advises:

“In July 2025, Homes Tasmania reviewed its pipeline to re-categorise projects and change how land is counted. Land will only be recorded as completed once sold. Homes Tasmania will track construction, and if a dwelling is not substantially commenced within two years, the lot will return to the pipeline until a housing outcome is achieved.”

Accordingly, Homes Tasmania made two changes to their reporting for July 2025:

- 314 affordable residential lots were moved from ‘completed’ back to the ‘current pipeline’ as those land lots have not yet sold.

- The ‘concept phase’ was removed altogether and the deliverables in that category were moved to the ‘current pipeline.’

TasCOSS notes that Homes Tasmania’s strategy of moving land lots between the categories of ‘completed’ and the ‘current pipeline’ when construction of a dwelling is not substantially commenced within two years has some drawbacks. This counting rule is likely to result in churn between the two categories and create confusion about what has actually been completed. A more transparent and straightforward counting rule would be to only count land lots in the ‘completed’ category once a house has been built on the land.

Figures 2.1 and 2.2: As at 31 October 2025, Homes Tasmania has only delivered 739 social housing homes towards its 2,000 social housing sub-target to be achieved by 30 June 2027. To meet this target, Homes Tasmania will need to build or purchase 1,281 homes in just under two years.

Figure 2.3: As at 31 October 2025:

- There were no crisis units in Homes Tasmania’s current pipeline because it has delivered on its target of 119 crisis units.

- 76% of deliverables in the current pipeline are affordable homes, affordable rentals or affordable residential lots, rather than social housing or supported accommodation.

- There are 2,650 affordable home purchases in the current pipeline, making up 26% of the 10,000 target.

Figure 2.4: According to Homes Tasmania’s Strategy, the composition of social and affordable homes in Tasmania will change significantly from their 2020 baseline figures to their final figures in 2032. The proportion of social housing and supported accommodation will decrease from 89% to 67% and the proportion of affordable housing will increase from 8% to 32%.

NB: Our calculations for Figure 2.4 don’t take into account any homes which may be lost between 2020 and 2032 (e.g. due to age, severe damage or environmental disasters).

Updated on 10 December 2025 with the latest available data.

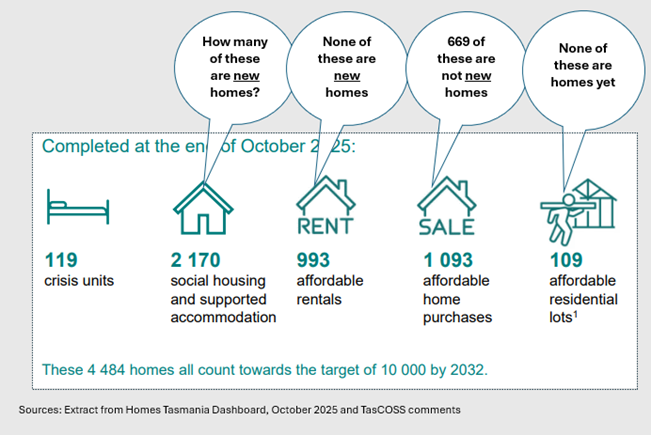

This infographic (above) shows that Homes Tasmania has made progress towards achieving its 10,000 target, but not all of what they have delivered is actually a home. As well, many of the deliverables are re-purposed homes rather than new homes — and therefore do not contribute to overall housing supply.

This infographic (above) shows that Homes Tasmania has made progress towards achieving its 10,000 target, but not all of what they have delivered is actually a home. As well, many of the deliverables are re-purposed homes rather than new homes — and therefore do not contribute to overall housing supply.

Updated on 10 December 2025 with the latest available data.

As at 31 October 2025, the completed total includes:

- 109 affordable residential land lots (without any homes on them).

- 993 affordable rentals for existing homes rather than new builds.

- 669 affordable home purchases for existing homes rather than new builds (see KPI 6, Homes Tasmania Dashboard for October 2025).

It is not clear how many of the social housing and supported accommodation delivered are existing homes that have been repurposed, rather than new homes.

As at 31 October 2025, Homes Tasmania has delivered a mix of 4,484 homes, residential land lots and crisis units. However, the actual number of homes and crisis units they have delivered is 4,375; and the number of new homes and crisis units delivered is, at most, 2,713.

The actual figure for new homes may be even lower if any of the social housing homes counted towards the targets are re-purposed homes rather than new builds.

Coming soon: TasCOSS will explore this further with Homes Tasmania and we’ll share our findings here.

In 2020, the Tasmanian Government committed to delivering 10,000 social and affordable ‘homes’ by 2032, including a commitment to deliver 2,000 social ‘homes’ between 2023 and 2027. Although Homes Tasmania is making progress delivering on these targets, unfortunately the impact on the housing crisis has been minimal.

This is evident in the growing numbers on the social housing waitlist; growing demand for homelessness services; and community organisations reporting worsening difficulties accessing safe, appropriate and affordable housing for their clients, which is intensifying their experiences of family violence, poverty and disadvantage.

Anglicare Tasmania delivers the Housing Connect Front Door service to Tasmanians seeking housing support. In 2024, Anglicare’s Social Action & Research Centre released service data demonstrating the need for more social housing beyond what’s already committed. Their research highlights that there is insufficient affordable housing available to meet the needs of over two thirds (69%) of clients seeking long-term, safe and affordable housing in this state. See: More houses needed: Housing Connect front door service snapshot, Anglicare Tasmania.

Is the modelling by Homes Tasmania, which presumably informed the housing targets, still reflective of need, noting the social and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and inflationary pressures? In the midst of a housing affordability crisis in Tasmania which has worsened since the two targets were set, they are unlikely to meet the current need for housing in this state.

There has been confusion expressed about what exactly the Tasmanian Government has committed to deliver. As we’ve highlighted (above), what has been delivered so far towards the 10,000 target is not always a home (e.g. residential land); and it’s not always a new home (e.g. an affordable rental or an affordable purchase of a pre-existing home). While it’s not unreasonable for Homes Tasmania to transition pre-existing housing into affordable housing or social housing, this won’t lift the overall supply of housing or boost housing construction activity in Tasmania.

TasCOSS is calling on the Tasmanian Government to:

- Better reflect housing needs by boosting the 10,000 homes and 2,000 social homes targets, in view of the acute housing shortage and very low housing affordability in Tasmania, especially for people on low incomes.

- Double the proportion of social homes and supported accommodation in their overall target, to reduce Homes Tasmania’s heavy reliance on affordable rentals and affordable homes to reach the target.

- Provide more clarity on their plans and funding mechanisms for all the homes and land lots in the current pipeline, to provide critical information to community housing providers and the housing construction industry.

Topic 1: Waiting for social housing

Demand for social housing has grown significantly over the last decade, and is outstripping new supply, as reflected in continued growth in the social housing waitlist.

Tasmania’s wait time for social housing for ‘greatest-need households’ is now the second highest in Australia, after the Northern Territory. See: Productivity Commission data.

This lengthy waiting period is putting financial, practical, relationship and emotional strain on many Tasmanians who urgently need access to safe, affordable and appropriate housing.

Recent research by Dr Catherine Robinson and others exploring people’s experiences of lengthy waits for social housing in Tasmania, New South Wales and Queensland found that waiting for social housing was detrimental to people’s health, wellbeing and safety. People described waiting a long time for social housing as horrible, demoralising, traumatic, nerve-wracking, tiring, dreadful, disappointing and soul-destroying. See: Waithood: The experiences of applying for and waiting for social housing, University of Technology Sydney.

Updated on 10 December 2025 with the latest available data.

Indicators:

As at 31 October 2025:

- There were 5,380 applicants on the social housing waitlist — the highest number ever.

- There are 622 homeless applicants on the social housing waitlist who are entirely without housing (e.g. sleeping in a tent or car). There are another 3,480 applicants staying in temporary or insecure accommodation, such as a shelter or they’re couch surfing.

- There are 707 applicants on the social housing waitlist who are ‘highest priority,’ which includes those leaving homelessness services, prison, hospital or out-of-home care.

- The average wait time for social housing for priority applicants (highest priority and standard priority) is 82.4 weeks, which equates to more than 18 months.

Figure 1.1: The number of applications on Tasmania’s social housing waitlist increased from 3,809 in January 2021 to 5,380 in October 2025. This is an increase of 41% over about 4.75 years.

NB: See our Glossary for explanations of:

- Different definitions of homelessness; and

- Priority categories used for the social housing waitlist.

Figure 1.2:

Tasmania’s social housing waitlist and wait times increased between 2020 and 2024:

- The number of ‘highest priority’ applicants increased by 73% from 406 in 2020 to 707 in 2024.

- The number of ‘standard priority’ applicants increased by 30% from 2,390 in 2020 to 3,098 in 2024.

- The number of all applicants increased by 41% from 3,373 in 2020 to 4,745 in 2024.

- The number of people on the social housing waitlist increased by 34% from 6,197 people in June 2020 to 8,273 people in July 2024.

NB: See our Glossary for an explanation of the number of applicants versus the number of people waiting for social housing.

It is unacceptable that Tasmanians are waiting for many months or even years on the social housing waitlist before being allocated a home. Moreover, Tasmanians are waiting longer on average for social housing than people in other states and territories.

This means that, for many Tasmanians, social housing is currently not a realistic solution to their housing insecurity, and many are continuing to struggle in overcrowded, unsafe or unaffordable housing — or sleeping rough.

There is an urgent need for new social housing in Tasmania in addition to what has already been committed. Many organisations, including Shelter Tasmania, the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) and Everybody’s Home, have called on governments to deliver more social housing to achieve a target of 10% of all dwellings in Australia being social housing. Homes Tasmania has committed to delivering around 3,100 social housing dwellings by 2032 — that’s far too few to meet the growing demand in Tasmania.

TasCOSS is calling on the Tasmanian Government to:

- Take targeted action to significantly reduce the number of applications and people on the social housing waitlist, and reduce the average wait time for social housing for priority applicants.

- Commit to an accelerated program of delivering more social housing, including a clear pathway to social housing being 10% of all dwellings in Tasmania.